How do you write a good science fiction novel?

Talk about a big question. You could fill up a college semester or two answering that one. You could write a series of books on the subject.

But let’s tackle it anyway, shall we? Let’s look at some of the steps you can take in your quest to write a good, or even great, sci-fi novel.

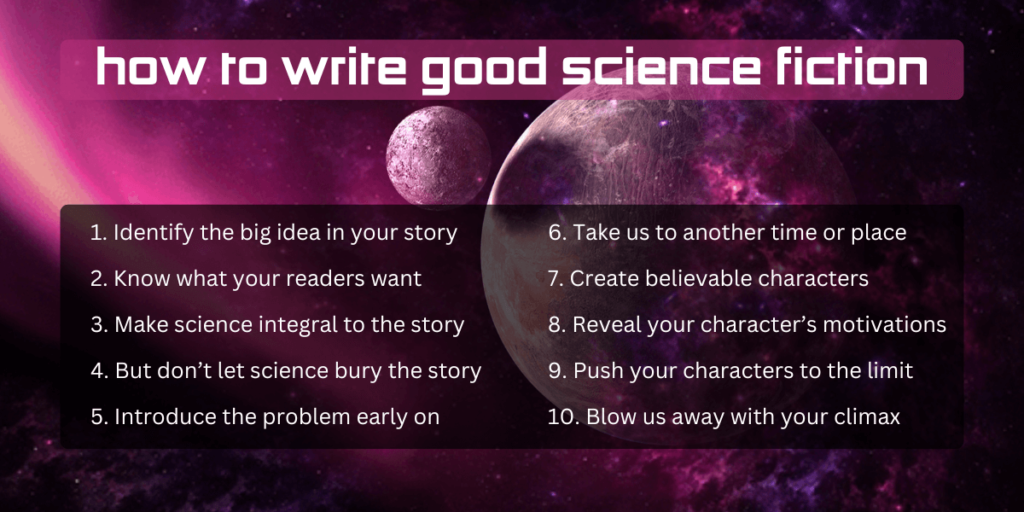

10 Steps to Writing a Science Fiction Novel

I spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to structure this article, what to include, what to leave out, etc. Ultimately, it came down to the following ten points:

- Identify the ‘big idea’ in your story

- Know your readers and what they want

- Make the science integral to your novel

- Don’t let science overwhelm the story

- Show us your character’s motivations

- Introduce the problem early on

- Create believable characters

- Take us to another time and place

- Push your protagonist to the limit

- Blow us away with your climax

If you check all ten of the boxes above — or even most of them — you’ll be well on your way to writing a good sci-fi novel.

1. Identify the ‘big idea’ for your story.

For well over a hundred years, readers have turned to science fiction to find big and bold ideas brought to life. And the sci-fi genre has delivered with a steady outpouring of grand concepts.

As a writer of science fiction, you’ll want to spend some time thinking about the thing that makes your story different and special. I refer to this as the “big idea.”

Sci-fi readers will expect it from you. They’ll look for it within the first chapter, in most cases. So you’d better deliver.

The best way to get a feel for this concept is to read lots of science fiction novels. Think about the last book you really enjoyed. Did it have a big idea or premise? I’m willing to bet it did.

So, writing a good science fiction novel starts with the idea. That’s the seed from which the story grows. It doesn’t end there, of course. There’s a lot more work to be done, as we will cover in steps 2 through 10 below. But the big idea, the novel premise that will set your work apart, has to be there from the very beginning.

In other fiction genres, the big idea is less important. In “literary” or mainstream fiction, for example, it might be enough to have interesting characters face challenges and change or grow as a result of them. But with a sci-fi novel (and with speculative fiction in general), you need to deliver something more. You need a big idea.

Don’t get me wrong: It’s also important to have interesting characters who face challenges that change and shape them. That’s good for all genres. That’s the core ingredient of any good story. But science fiction needs a big idea, on top of those other ingredients.

Here’s the good news. The sci-fi genre is incredibly diverse. It offers writers an endless array of paths and possibilities, any of which could lead to a good book. That’s partly why it’s one of the most popular genres of fiction today. There’s always room for innovation and fresh ideas.

2. Know who your readers are and what they want.

Science fiction readers are as diverse as the books they read. Everyone has different expectations when they start a new novel. But when it comes to sci-fi, readers tend to look for specific elements when they pick up a novel.

For example, take the whole “hard” versus “soft” thing:

- Hard science fiction gets into the “nuts and bolts” of whatever science appears in the story. Hard sci-fi stories often deal with some aspect of astronomy, biology, chemistry or physics.

- Soft sci-fi is typically more concerned with the societal and human aspects of the story, spending less time on the technical or scientific. These stories often feature the “softer” sciences like anthropology and psychology.

This is a bit of an oversimplification. (If you really want to drill down into the granularity of this distinction, check out this article on Tor.com.) But it helps to illustrate the point I’m making here.

Some sci-fi readers will gladly consume books across the entire spectrum, while others prefer to stay within a narrower lane.

Let’s look at Andy Weir’s novel The Martian. I consider this book to be “hard” science fiction, because it mainly deals with problem-solving of a scientific nature. It appeals to be people with an interest in physics, engineering, etc. It appeals to left-brained people.

But it didn’t appeal to me. I like to read sci-fi novels with more humanity in them, stories with deep and complex characters. For me, the astronaut / protagonist Mark Watney was little more than a literary “voice” used to explain scientific obstacles and solutions. I didn’t connect with him at all. Same for the other characters in the story.

Of course, my dislike for the novel didn’t hamper its success. It hit the New York Times best-seller list and stayed there for several weeks. It spawned a successful movie adaptation. That’s because it did appeal to legions of fans, readers who like a certain type of sci-fi story.

Ultimately, you have to tell the story that’s burning inside you, the one screaming to get out. You have to be true to yourself and to the story you want to tell. That’s first and foremost.

At the same time, it helps to think about the kinds of readers you want to attract, and the expectations they might have. This can be accomplished, in part, by reading widely within your chosen subgenre. You have to know what’s out there, so you can make sure your own work measures up.

3. Make the science integral to the story.

The definition of science fiction can vary depending on who you ask. But most readers and writers agree on one thing. A good sci-fi story or novel has to feature science in a way that’s integral to the story. That’s the bare-minimum requirement and definition.

The story doesn’t have to be “about” the science. In fact, it probably shouldn’t. It should probably be about the main character(s) you’ve created. It should be about what those characters want, and the enormous obstacles they face in pursuit of their goals. That’s the heart of the story.

But this is science fiction we’re talking about here. So the scientific component has to be there in some way, even if it’s in the background.

4. But don’t let the science overwhelm the story.

At their core, novels are about characters and the things that happen to them. This is true for science fiction, fantasy, romance, mystery and other genres as well. We read stories to discover new worlds and to connect with the people who inhabit them. We join the characters on their journeys, rooting for them along the way.

This is something to bear in mind, as you set out to write a science fiction novel.

Even “hard” sci-fi novels, those that dig deeper into the scientific aspects, have to be relatable. As readers, we might not fully understand the complexities of interplanetary travel, or artificial general intelligence. But we do know what it means to be human. We have years of experience in that department.

So while we might struggle to keep up with the science at times, we can always relate to the human side of the story.

What if your novel doesn’t feature humans? What if it takes place on another world populated by an alien race? The same thing applies! Even if your story lacks human characters — even if it’s set on the planet Extoor-13, where the dominant lifeforms crawl around on tentacles and absorb carbon for sustenance — we have to understand their wants, fears and hopes.

Because without those familiar and relatable qualities, you don’t really have a novel. You have the fictionalized version of a textbook. It can’t be all science. It has to be science fiction. There has to be a story we want to follow, with characters we care about in some way.

And speaking of relatable characters…

5. Show us your main character’s motivations, fears and concerns.

What does your main character want? What does the character want for those around her, for her loved ones?

If you can answer these questions, you’re on your way to writing a good science fiction novel. If you can’t answer them, you’ve got some more work to do. (And that’s okay. Novels are work!)

Much of storytelling comes from this basic concept. The main character wants something, but an obstacle presents itself. This leads to conflict, friction and drama. You can increase the tension and drama in your science fiction novel by “turning up” the want … by boosting the character’s motivations.

Consider the difference:

- A girl steals an apple from a vendor in a marketplace.

- An impoverished woman in a draconian society with harsh laws steals an apple from a cart to feed her starving daughter.

Notice the difference in tension here, the higher stakes that are involved. In the second example, the woman is risking her life to commit this petty crime. The “want” is stronger. In fact, it’s more of a need than a want. The obstacle is stronger as well. If she gets caught, she could be punished harshly, perhaps even losing a hand. Yikes!

But how do we know these things? How do we know what the character wants or fears, from one scene to the next? There are several ways to accomplish this. Interiority is one of them. In fiction writing, interiority refers to a character’s thoughts, fears and reactions to the world around her — the character’s inner thoughts.

We can also discover a character’s motivations, fears and concerns through dialogue and action. In the apple example from earlier, we know the woman is desperate simply by observing her behavior. But the author could give us more insight (and thus a deeper connection to the story) by revealing the woman’s inner thoughts.

Here’s an example of how that might play out:

Maida stared at the fruit stand for some time, clenching and unclenching her hands. She thought of her daughter’s rumbling belly. Could the girl make it another day with nothing to eat? Or would the coming night be her last? She was so thin, so frail already! And who would miss a single apple from a cart stacked with them? Would the vendor fall into poverty over the loss of one apple? Of course not. That shining crimson sphere meant everything to her and so little to this man. It was one of dozens. Hundreds even. Of course, there was the law to think about. Maida had heard it said that, under the new regime, thieves often lost the hand that did the stealing as punishment for their crimes. She thought of that. She thought of her daughter. She waited until the vendor was busy haggling with a customer, and then made her move…

From this brief passage (that I made up), we gain a lot of insight into Maida’s current situation and how it drives her motivations. We learn she is willing to risk a harsh punishment to care for her daughter. What she’s about to do is wrong — but right at the same time. And all of this is done through interiority.

6. Introduce the ‘problem’ or conflict early on.

If your protagonist is having a good time, the reader is not.

You’ve probably heard that maxim before, or some variation of it. It’s common advice offered in countless creative writing classes and handbooks. And there’s some truth to it. A lot of truth, in fact.

In his insightful book Immediate Fiction: A Complete Writing Course, author and writing coach Jerry Cleaver expresses this idea in simple mathematical terms:

“Want + obstacle = conflict”

If you want to write a good science fiction novel, you have to create obstacles for your characters. You might not want to do this. After all, you like your characters. You created them from nothing. They are your literary offspring. Why would you want to see them suffer?

But you need to do it. They need to face challenges at every turn. It is through these challenges that your characters grow and change.

When your characters encounter challenges within the story, it creates drama. And drama keeps us turning the pages to find out what happens next.

When people say things like, “I could not put this book down,” it’s usually because of the conflict and drama. Those are the bones of your story. Those are the go-to elements you use to keep the reader engaged in the novel.

7. Create believable characters we can relate to.

Some writing instruction books and articles claim that a main character doesn’t have to be likable, as long as they’re relatable. According to the authors, the reader doesn’t have to like the protagonist, as long as they can understand the character’s motivations.

That might be true. But for a beginning writer, I think it’s important to create a character that’s likable in at least some way.

To stay connected to a story, we have to care about the characters — or at least the main character — on some level. We have to understand, and maybe even share, their hopes and fears.

We might not agree with the actions they take in pursuit of those goals. We might even shake our heads and say, “What the hell are you doing?” But we have to relate to the character’s motivations.

In the apple-stealing scene from point #5 above, we encounter a character who is about to commit a crime. On the surface, this is a bad act that should earn our disapproval. We should look down on it. But then we learn about Maida’s motivations, her hungry daughter at home, her desperation, and we understand why she is doing it. We relate to the reasoning behind the act. Maybe we can see ourselves doing the same thing, if the shoe were on the other foot.

If you can get readers to relate to your characters in some way, you’re well down the path to writing a good science fiction novel.

8. Take us to another time and place.

People don’t read science fiction to encounter a world exactly like their own. In fact, that’s the exact opposite of what they’re expecting when they crack the spine (or tap the cover) of a sci-novel.

They want to be swept away from “life as we know it” … away from the real world with its hassles and drags. They want to be whisked away to a time and place unlike any the’ve seen before. If you want to write a good science fiction novel that resonates with readers, you’ll want to foster a sense of wonder.

- Phillip K. Dick took us to a post-apocalyptic version of San Francisco where human bounty hunters track and “retire” rogue androids. (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?)

- Ann Leckie told us the story of a spaceship’s artificial intelligence who becomes trapped in a human body and sets off on a quest for revenge. (Ancillary Justice)

- Frank Herbert took us to a desert planet called Arrakis, where workers mine a special kind of “spice” used for drug production. (Dune)

These stories pull us away from the familiar and plunge us into new worlds. They open our minds to alternate realities. They awaken something inside us, just by being different.

Dune and Do Androids Dream have already earned science fiction “classic” status. Ancillary Justice, a much younger novel, is well on its way to that designation. We would do well to learn from these stories, and from their big ideas.

9. Push your character(s) to the limit, emotionally and physically.

Vladimir Nabokov, author of Lolita, once described the novel-writing process in this way: “The writer’s job is to get the main character up a tree, and then once they are up there, throw rocks at them.”

There is much truth in this pithy little statement. In fact, we’ve covered this concept already. Your main character has to face great challenges during the course of your story. If they do — and if you’ve done a good job creating believable characters — readers will remain engrossed in the story straight through to the end.

If you don’t hurl figurative “rocks” at your characters, the reader will lose interest. Remember: If your protagonist is having a fine time, the reader is not.

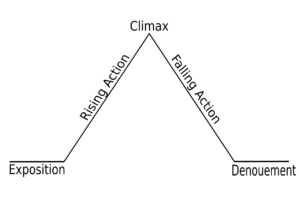

I’ve seen the “tree and rocks” metaphor applied to the three-act structure of plays, a structure that can also be used when writing a science fiction novel:

- Act one: Exposition and inciting incident (character starts up the tree)

- Act two: Rising action and climax (you throw rocks at the character)

- Act three: Falling action and resolution (character gets down from the tree)

This is an oversimplification, but you get the idea. Many works of fiction follow this very same model.

To write a good science fiction novel, you have to push your characters like they’ve never been pushed before. You have to take them outside of their comfort zones. The challenges they face in the story (including the threat from the antagonist) has to be a defining moment in their lives. It has to be big.

10. Blow us away with your climax.

As readers, we tend to remember the climax and ending of a novel long after finishing it. These things resonate with us, but for different reasons.

We remember the ending for structural reasons. It’s the last thing we read. We remember the climax, because that’s where the fireworks go off. It’s the most exciting part of the story, and so it stays with us long after.

But what is a climax, exactly? Here are a couple of dictionary entries that define it well:

- Merriam-Webster: the point of highest dramatic tension or a major turning point in the action.

- Cambridge Dictionary: the most important or exciting part in the development of a story or situation, which usually happens near the end.

The climax is an important part of any novel. Without one, stories tend to seem flat. In fact, that’s exactly what a climax does — it prevents your story from being flat. It gives you a peak or apex to work toward, as you’re writing your novel. That applies to all genres of fiction.

But I would argue that a big climax is even more important for science fiction writers, and speculative fiction in general. In a sci-fi novel, you’ve already started with a big idea. You’ve “wowed” us with your world building, with your unique vision. In order to go up from there — in order to reach the climax of the story — you have to climb pretty high. Higher than a writer of literary fiction.

There are many ways to structure a sci-fi novel. Whatever method you use, you should always have a highpoint of the action — a culmination when all of the shit hits the fan, dramatically speaking.

There are several reasons for this. Here are the two most important ones: Readers expect it, and it makes the story more memorable.

So there you have it, a ten-point plan for writing a damn good science fiction novel. Grab your pencil or open your laptop. Start at the beginning. Show us whose story it is. Show us what they want, and what obstacles stand in their way. Create a “big idea” that will sweep us away to another time or place, a world unlike our own. Push your characters to their limits. Force them to adapt, to change. And end with a bang!

Angela

Fantastic. These tips have helped me so much. Please keep posting this wonderful Sci Fi content. I’m a huge sci fi fan and id like to show u my work for feedback. Ile tell my year 8 students these tips.

Mauro

I’d very like to know how can I do to modify (virtually) a city or a single existing building in a sci-fi version respecting a specific territorial culture.

Is there any easy way?…. Any app about it?